Why studying India’s roads matters for Australia’s international relations

By: Luis Perez

Posted on

As one of Australia’s key trading partners and regional allies, India’s rise as a global economic powerhouse remains a topic of much debate. ANU historian Aditya Balasubramanian is hoping to contribute to this discussion by conducting the first-ever study of post-colonial roadbuilding in the South Asian nation.

The globe’s most populous country, India, is wrestling with a colossal challenge: delivering economic prosperity for 1.4 billion people while curbing the environmental cost of its expeditious development.

Being home to 39 of the 50 most polluted cities in the world, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070, but roadbuilding remains a critical area of focus in his national agenda – a priority which stands in the way of climate targets.

The government’s push to connect every village by road by 2027 has triggered a surge in motor vehicle registrations, driving up emissions from transport, which already account for nearly 15% of India’s carbon footprint.

But how can nations balance bold climate ambitions while sustaining relentless economic growth?

Dr Aditya Balasubramanian, from the ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, doesn’t have the answers to this conundrum, but he is ready to dig into the past to find clues.

By examining how India, in less than 80 years, went from 170,000 km of road mileage to 6 million, he is poised to explore the ripple effects of such growth – both on the economy and the environment.

His findings could help us better understand how Australia’s fifth largest trading partner has changed economically and environmentally over the last century, deepening knowledge of the Indo-Pacific region in an era of shared global challenges.

History on wheels

Today, the echoes of history and the pulse of modernity converge on Indian roads as bullock carts and cycle rickshaws share space with electric two-wheelers and roaring trucks.

Balasubramanian highlights the peculiarities of India’s largely post-colonial and uneven industrialisation process.

“India’s industrialisation took place in the context of a post-colonial society, inheriting a state apparatus tooled for the extraction from the colony and for the benefits of the motherland,” he says.

“Although the big contemporary national highway projects dominate the headlines, most of the road network in India began developing in 1947, reason why most of them are village and district roads.”

This year, Balasubramanian received funding from the Australian Research Council to study the history of Indian roads between the 40s and the 70s — a period of exponential growth.

To do so, he will travel to four different regions of the country—each a window into the past that will reveal how roads have shaped India’s economy, environment and society.

“As far as I know, there is no existing historical treatment of road building or road transport in India in the literature,” he says.

“Roads play an important role in the history of urbanisation. They not only provide conduits of mobility for people to work elsewhere and then return home, but have also revolutionised food distribution and disrupted life for animals.

“What really excites me about the prospect of traveling on these roads is the experience of meeting people along the way. I think that will give me something unique that cannot be found in historical archives.”

Balasubramanian, who published his first book,Towards a Free Economy, in 2023, feels adequately prepared for the task.

“My previous work has given me a good foundation to understand mid-20th century India and the focus of this project,” he says.

“It has also indicated to me the importance of spending long and sustained periods of time doing field work.”

A road to sustainability

While the electric vehicle (EV) revolution is gaining traction, the foundation of India’s energy sector remains coal—a resource that fuels both its industrial ambitions and its climate woes.

Balasubramanian expects his research to shed light on new sustainable ways to reimagine the future.

“Magic bullet solutions like moving to electrical vehicles come with a lot of unintended consequences. Most of the electricity used to power EVs in India is actually being generated from coal,” he explains.

“That’s why I’m interested in looking at alternatives like public bus transport or innovations like collective uses of cars.

“A lot of the social and scientific literature on climate often focuses on depressing tales about human hubris and the destruction of society. While I think that plays a very important role in sensitising us about the emergency before us, it does not necessarily give us tools to think about alternate possibilities.”

Balasubramanian hopes that his research insights drawn from India’s history can inform our understanding of other regions in the Global South as they navigate their own infrastructure policy paths.

“I'm hoping to open a dialogue with people who are working on public infrastructure in other parts of the world,” he says.

“In the third year of the project, I am planning to bring scholars and policymakers together in a symposium where we can all share our findings.”

Roadwork diplomacy

Australia and India stand as unequivocal strategic partners with their bilateral relations steadily “growing” , a fact underscored by the recent meeting between Prime Ministers Anthony Albanese and Narendra Modi at the G20 summit.

Against a backdrop of deepening ties, Balasubramanian points out that the history of India’s roadbuilding can be of tremendous value for Australia.

“Australia is involved through Australian Aid and other kind of institutions in many infrastructure projects in other parts of the world, particularly in the Pacific Islands,” he says.

“Understanding India’s successes—and missteps— in roadbuilding offers valuable lessons for the Australian government.

“I also think it's important for policymakers and the public sphere to have access to good social scientific research on how exactly our trading partners work.

“One of the distinctive strengths of The ANU historically has been that we have been one of the world's most outstanding centres for the study of the Asia-Pacific region. There's no telling how important this has been for the government from the postwar period to the present.

“I hope my research can follow from this long genealogy, aimed at ensuring Australia has informed relationships with key actors in the region.”

You may also like

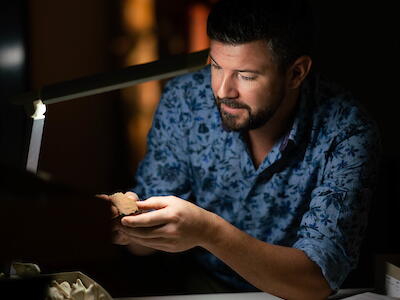

Reuniting communities in Papua New Guinea with long-lost burial pots

Stolen pottery provided Dr Ben Shaw the opportunity to right historical wrongs and create an archaeological field school to teach ethical research practice.

Bridging Korea and Australia: The Role of the ANU Korea Institute

As a hub for pioneering research, the ANU Korea Institute is offering valuable insights and fostering meaningful partnerships between Korea and Australia.

ANU Indonesian politics expert named as Australia's top researcher in Asian studies and history

ANU Associate Professor Marcus Mietzner is named in The Australian’s 2025 Research magazine as Australia’s top researcher in Asian studies and history.