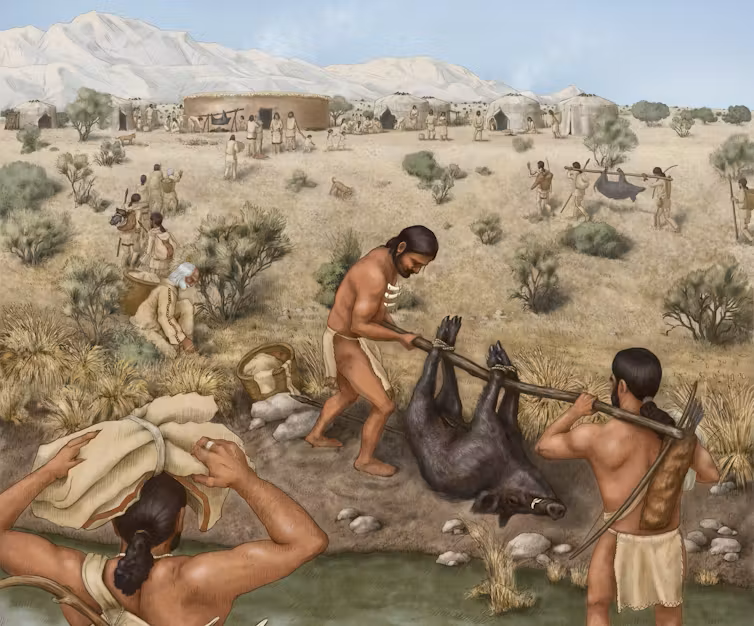

Communities arriving at the Early Neolithic site of Asiab with wild boar for a communal feast. Illustration credit: Kathryn Killackey

Have you ever stopped by the grocery store on your way to a dinner party to grab a bottle of wine? Did you grab the first one you saw, or did you pause to think about the available choices and deliberate over where you wanted your gift to be from?

The people who lived in western Iran around 11,000 years ago had the same idea – but in practice it looked a little different. In our latest research, my colleagues and I studied the remains of ancient feasts at Asiab in the Zagros Mountains where people gathered in communal celebration.

The feasters left behind the skulls of 19 wild boars, which they packed neatly together and sealed inside a pit within a round building. Butchery marks on the boar skulls show the animals were used for feasting, but until now we did not know where the animals came from.

By examining the microscopic growth patterns and chemical signatures inside the tooth enamel of five of these boars, we found at least some of them had been brought to the site from a substantial distance away, transported over difficult mountainous terrain. Bringing these boars to the feast – when other boars were available locally – would have taken an enormous amount of effort.