Extremely slow rocks deep in the ocean

I am on a hunt for stardust on Earth. Previously, I’ve sifted through snow in Antarctica. This time, it was the depths of the ocean.

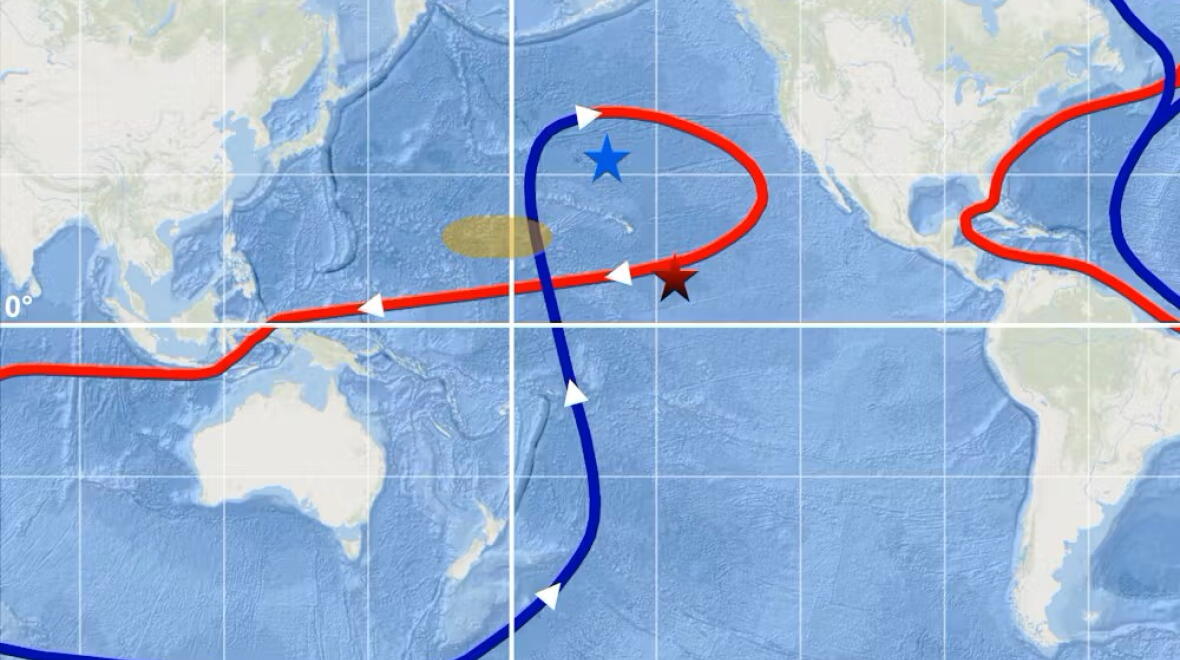

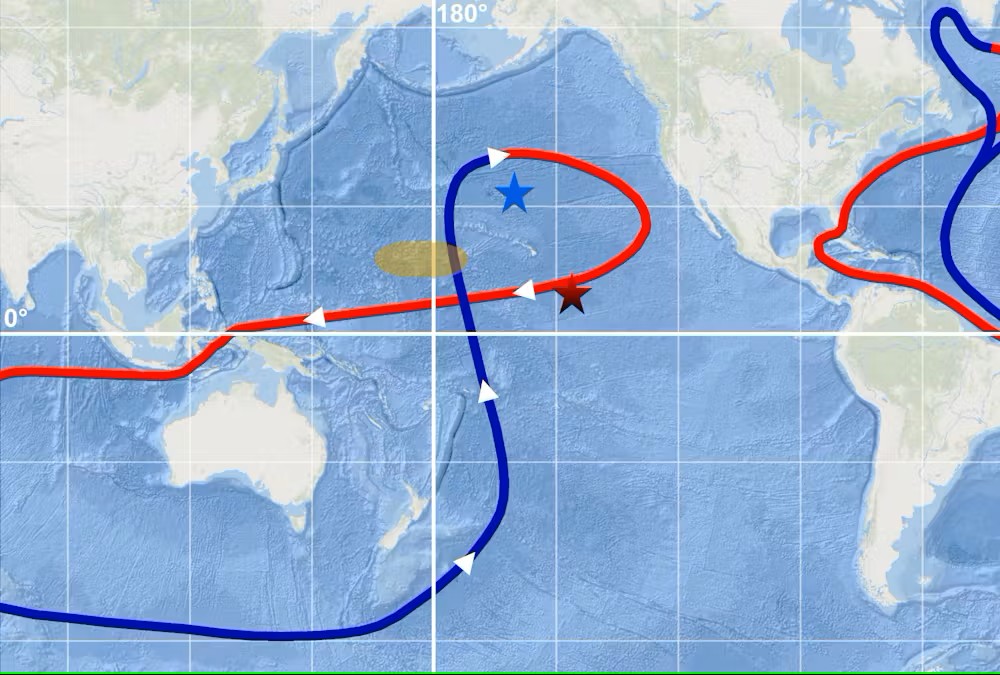

At a depth of about 5,000 metres, the abyssal zone of the Pacific Ocean has never seen light, yet something does still grow there.

Ferromanganese crusts – metallic underwater rocks – grow from minerals dissolved in the water slowly coming together and solidifying over extremely long time scales, as little as a few millimetres in a million years. (Stalactites and stalagmites in caves grow in a similar way, but thousands of times faster.)

This makes ferromanganese crusts ideal archives for capturing stardust over millions of years.

The age of these crusts can be determined by radiometric dating using the radioactive isotope beryllium-10. This isotope is continuously produced in the upper atmosphere when highly energetic cosmic rays strike air molecules. The strikes break apart the main components of our air – nitrogen and oxygen – into smaller fragments.

Both stardust and beryllium-10 eventually find their way into Earth’s oceans where they become incorporated into the growing ferromanganese crust.

One of the largest ferromanganese crusts was recovered in 1976 from the Central Pacific. Stored for decades at the Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources in Hanover, Germany, a 3.7kg section of it became the subject of my analysis.

Much like tree rings reveal a tree’s age, ferromanganese crusts record their growth in layers over millions of years. Beryllium-10 undergoes radioactive decay really slowly, meaning it gradually breaks down over millions of years as it sits in the rocks.

As beryllium-10 decays over time, its concentration decreases in deeper, older sediment layers. Because the rate of decay is steady, we can use radioactive isotopes as natural stopwatches to discern the age and history of rocks – this is called radioactive dating.